During the pandemic, I created this folder on my laptop, titled “I miss home.” It is a collection of images, sketches, and ponder of the reasons the experience of home is incomparable.

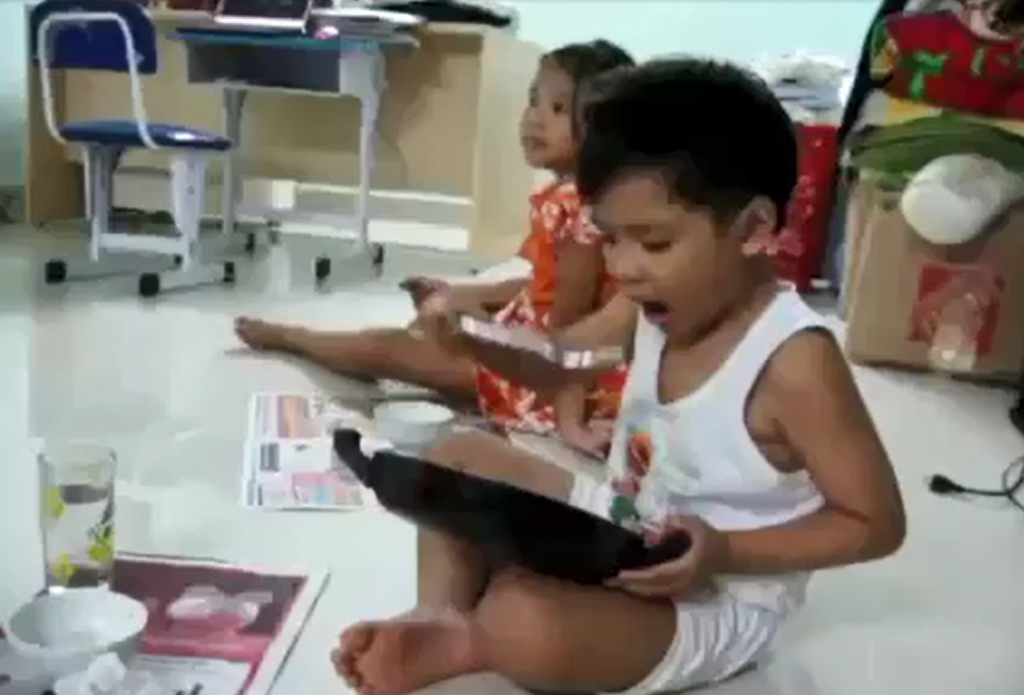

I stumbled upon this video when the 8-year-old me and 5-year-old brother were eating dinner while our renovated home was still in construction. While I was enjoying watching TV, my brother was intensely focusing on devouring the pan.

I remember on that day, my aunt, who is the chef of the extended family in the neighborhood (my small family move away 6 years later), cooked a delicious pork belly dish called “thịt rim” as shown. After the meat is gone, we were left with the sauce which marinated the meat. As Vietnamese, what we usually do is to add more white rice into that pan, coated every grain of rice in that sauce, and enjoy the rice until the pan is virtually cleansed. This way of eating is often time a means of frugality, since the rice will be seasoned to taste without extra ingredients and cooking.

Yet, the footage speaks to me rather differently: my brother has no incentives to save as such, he was enjoying the rice! With that, the dish appeals to me as a powerful tool to understand the culinary culture of my home country (Vietnam). Hence, introducing to you, a genre of Vietnamese food – braised side dishes – those that is cooked in the same template of technique, has the same flavor, yet is addictive until the very last smidge of sauce.

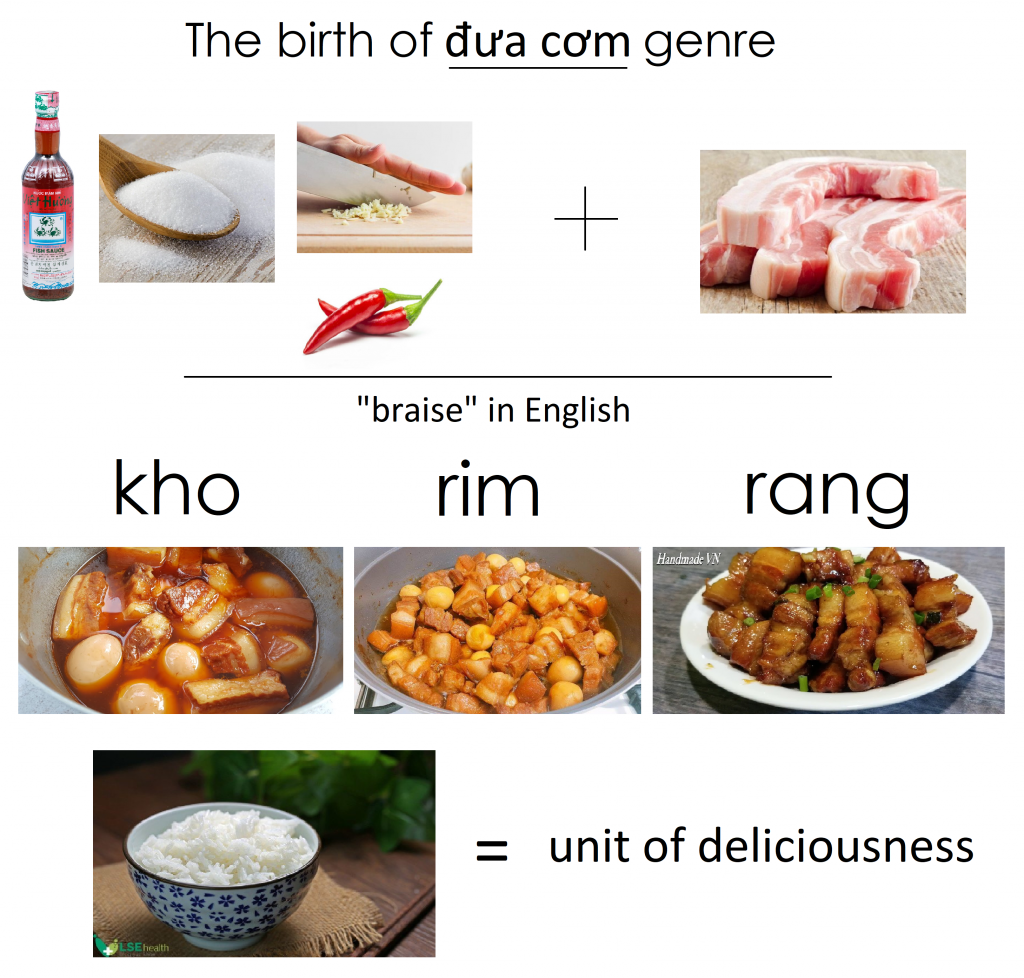

First of all, “braised” is an overly simplified term. As an English word, it does not refer to the same cooking methods in Vietnam. The Vietnamese “braised” consists of various techniques of stove-simmering a protein in its marinated condiment that you can find below – kho, rim, rang – which respectively reduce in water content. the kho sauce is like a well flavored soup you can dip your bread in, the rim sauce is the most perfect one for rice mixing, and the rang sauce is for those who enjoy the texture of fried rice when mixing in.

The ingredient for the marinated condiment involves fish sauce, sugar, garlic, and Asian chilis with ratio depending on regions. The Northern region, the historical avatar of Vietnam, emphasizes on the balance of taste, thus affixed with their umami ratio. The South enjoys sweetness as a fruity region, thus more sugar. And the middle region where I am from, due to harsh geographic hence climatic condition, prefers more fish sauce and chilis as a way to compact more saltiness and seasoning into fewer protein ingredients. Regardless of these differences, all these dishes always result in a saucy aftermath that the Vietnamese frugal way of life make a dish on its own. And trust me, you would always have to measure how yummy they are by the unit of rice bowl.

I realize that this academia-deserving topic could not be fully articulated in this short blog entry, so I’ll save it for another episode. To conclude, what I realize is that you can never truly replicate this dish in a Western settings. The hustling, individualistic, and sufficient way of life over here contrast the philosophy required in this culinary practice: tenderness, communal, and enjoyability. But soon, in a month, I’ll be able to enjoy this dish again, at home – its birthplace and its meaning-making vessel. Let me know if you enjoy a film about it ^^